Storm's Sound, Abstractions's Outcry

The first time I encountered Mark Bradford’s work was at the U.S. Pavilion of the 2017 Venice Biennale. Among countless international artists, the reason I couldn’t forget him was the visual shock delivered by his use of paper collage - an otherwise familiar method—expanded into an entirely different dimension.

Past a narrow entrance, a massive form descended from the ceiling to the floor, dominating the space. Its surface- made of tangled posters, flyers, and map fragments - evoked festering wounds, metaphorically referencing the social scars of the city. It conjured the image of a virus spreading across an urban landscape. On a stage symbolising national identity, Bradford boldly exposed the wounds and inequalities within American society to the eyes of the world.

Eight years later, the artist has gained international acclaim and now holds his first large-scale retrospective in Korea.

In harmony with the scale of the museum’s ceiling and floor, his work approaches the audience in a more refined and intimate manner. Upon entering the massive installation Float (2019), which spans approximately 600 square meters, one is met with colorful strings and worn paper layered across the floor like geological strata. The ground beneath your feet is uneven, textured like earth itself, while overlapping stripes of linear patterns evoke the velocity of fast-flying flyers and advertisements.

Each step feels oddly unsteady, like the precarious sensation of trying to balance on a wooden plank. At the same time, the work recalls the dazzling speed and density of urban Los Angeles, much like the bustling movement of airplanes in a daytime airport.

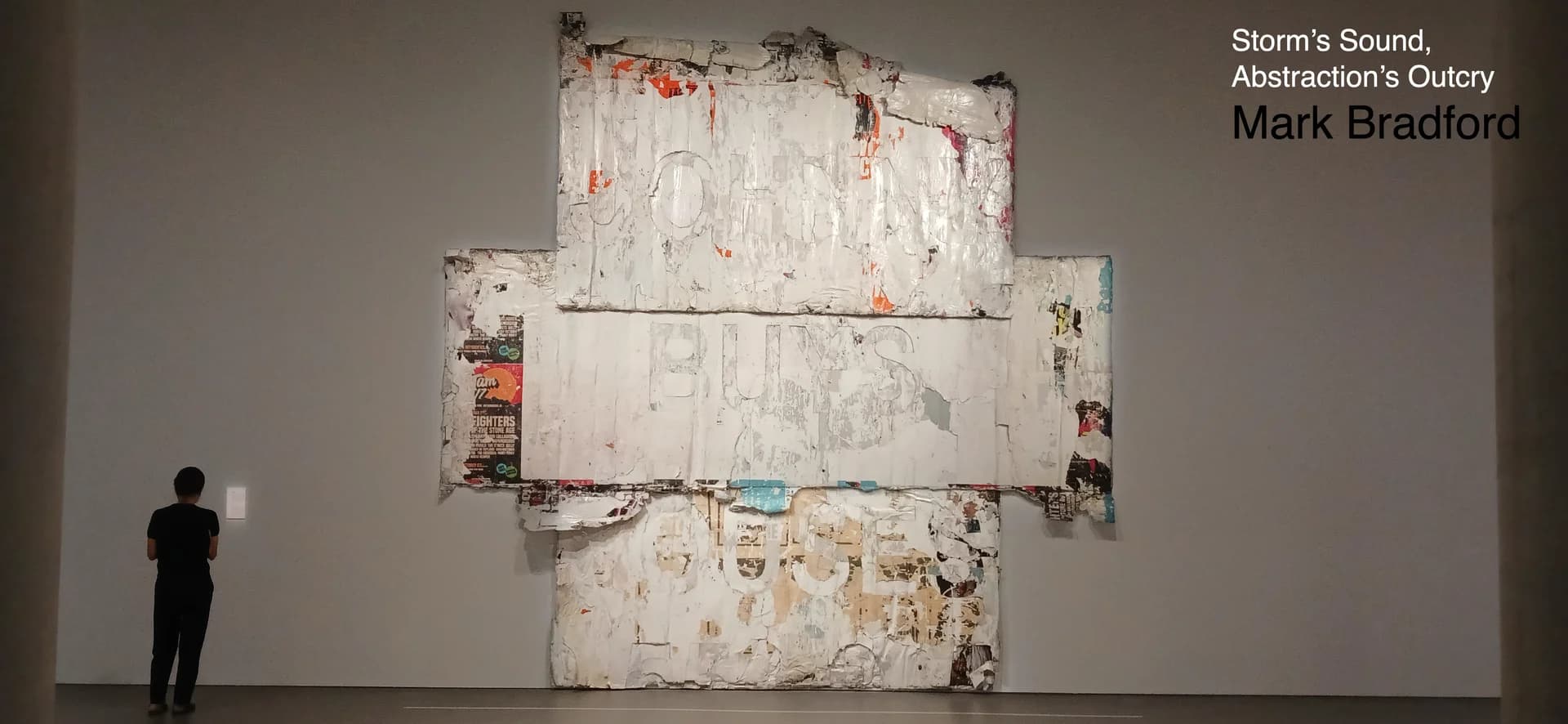

The work titled Manifest Destiny (2023) is a monumental paper collage that confronts viewers with the phrase “JOHNNY BUYS HOUSES” arranged like a cross. The term “Manifest Destiny” originally referred to the 19th-century political ideology used to justify American continental expansion. It first appeared in the media and political discourse, but it was never a neutral phrase—it was ideological language that glorified state violence and colonialism.

The phrase “JOHNNY BUYS HOUSES,” which appears on the surface of the work, is a familiar advertisement seen throughout urban neighborhoods, promoting quick house purchases at low prices. By overlaying the national myth of “Manifest Destiny” with this capitalist urban slogan, the artist exposes the continuity between past colonial exploitation and present-day gentrification. The piece suggests that the historical displacement of Indigenous people follows the same trajectory as today’s urban policies that drive out Black communities.

In this way, Bradford expands the geographic and historical context of the Black community in South Central LA, where he grew up. Most residents of this area were part of the so-called Great Migration, when Black populations moved from the racially segregated South to northern and western cities in the early to mid-20th century. Today’s gentrification, which dismantles Black neighborhoods, echoes the historical dismantling of Black communities in the South through forced relocation, land seizure, and lynching.

Ultimately, Bradford reveals how the Black communities of LA have inherited the structural racism and economic marginalization rooted in the American South.

Although the word “South” does not appear explicitly in the work, elements such as the use of Haint Blue (a color traditionally painted on slave quarters), the unstable housing conditions of Black communities, and the repeated phrase “Johnny Buys Houses” suggest that the legacy of Southern racism continues to operate within the urban spaces of present-day Los Angeles. In other words, the artist uses the specific reality of LA as a medium to reveal how the history of racial discrimination and structural oppression in the American South is reproduced in today’s urban landscapes. In this context, his work can be read both as a “regional record” and as an “abstraction that engages with social memory.”

For his solo exhibition at the Amorepacific Museum of Art, the artist presents a new series titled The 'Storm Is Coming(2025)'. The gestures of the figure “Swan” in the work borrow from the performance vocabulary of Black and queer communities that emerged within ballroom culture. Through this reference, the artist recalls the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina, which struck the American South in 2005. At the time, government incompetence and delayed rescue efforts resulted in numerous deaths, with the burden of the disaster falling disproportionately on impoverished Black communities.

Ballroom culture originated in the mid-20th century as a defiant and creative stage crafted by Black and Latinx LGBTQ+ communities to assert their existence in the face of discrimination. The artist translates Swan’s dramatic ballroom gestures—arched arms, contorted movements—into sweeping lines, bold brushstrokes, and overlapping curves, abstracting the choreography into marks of motion across the canvas.

Layered with stenciled lyrics by Kevin JZ Prodigy, the gestures in the work transcend mere movement, expanding into a collective expression imbued with language and rhythm. In this way, the traces of the body and the lyrics overlap, transforming dance and language into a corporeal vocabulary that seeks to break through the oppressive force of social disasters.

The exhibition space, covered entirely in black paper to emphasize the seven large-scale canvases, delivers an overwhelming and visceral experience. As the title suggests, the black walls evoke the roaring winds and destructive force of a storm. The visual texture of the collaged surfaces—built up through pasting, scraping, and sanding—translates Swan’s gestures into the sound of a storm, evoking a collective outcry. It becomes a sonic and visual embodiment of the cries for help, the rage, and the despair experienced by Black communities during Hurricane Katrina.

After viewing the exhibition, I was reminded of meongseok-mal-i, a brutal form of punishment from the Joseon Dynasty. This association emerged from the sensory memory of the concealed body being replaced by a bundled, textured mass—much like the “meongseok,” a straw mat in which slaves or criminals were rolled up and collectively beaten. A frequent image in historical Korean dramas, this form of punishment symbolizes the structural violence inflicted by a rigid caste system. Though it may appear outwardly as an anonymous, nameless mass, the moment the mat is unrolled and the body is revealed, the concealed pain and anonymized violence become starkly visible—mirroring how historical trauma can re-emerge in contemporary struggles with class inequality, labor exploitation, and discrimination.

In response to the long-standing question in art history—“Can abstraction carry social meaning?”—Mark Bradford overlays the autonomy of traditional abstraction with the social data of the city and the voices from its margins, pulling abstraction back into the tensions and inequalities of the contemporary moment.

His abstraction is a resonating voice, a collective outcry. At the same time, it becomes a monumental visual structure that exposes urban realities and channels a new narrative force emerging from destroyed surfaces. Bradford does not merely represent the voices of the oppressed through abstraction; rather, he presents them as an overwhelming presence in their own right.

Yu Jihye, Contemporary Artist & Art Writer